How Custom Software is Built: A Step-by-Step Guide

In a world driven by digital solutions, businesses are constantly seeking a competitive edge. While off-the-shelf software offers a quick fix for common problems, it often falls short of meeting unique operational needs. This is where custom software, tailored specifically to an organization's processes, goals, and challenges, becomes a game-changer. It’s a powerful investment, but it can also seem like a complex and opaque undertaking. Understanding how is custom software built demystifies the process, empowering you to make informed decisions and collaborate effectively with your development partners. This comprehensive guide will walk you through the entire journey, from a simple idea to a fully functional and scalable application.

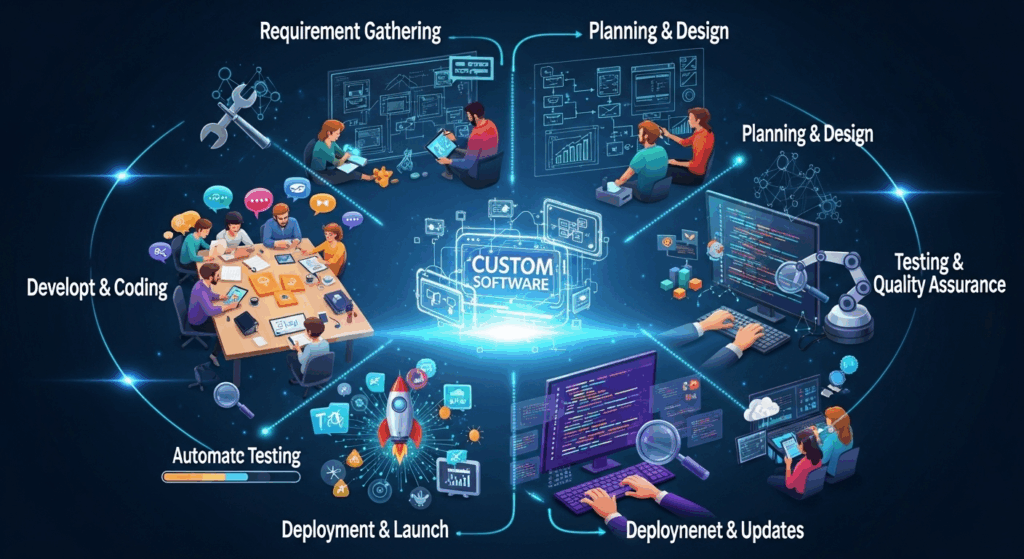

The creation of custom software is not a single event but a structured, multi-stage lifecycle known as the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC). Each phase has a distinct purpose, a set of deliverables, and requires close collaboration between the client and the development team. By breaking down this intricate process into digestible steps, you can gain a clear understanding of what it takes to transform a vision into a tangible digital asset that drives growth, efficiency, and innovation.

The Discovery and Planning Phase: Laying the Foundation

Before a single line of code is written, a solid foundation must be laid. The discovery and planning phase is arguably the most critical stage in the entire custom software development journey. It's here that ideas are vetted, goals are defined, and the project's entire trajectory is mapped out. Rushing through this stage or giving it insufficient attention is a common reason for project failure. This phase is all about asking the right questions: What problem are we solving? Who are the users? What is the desired business outcome? The goal is to achieve absolute clarity and alignment among all stakeholders.

During this phase, the development team works closely with you to conduct in-depth research. This involves stakeholder interviews to understand business processes, user needs, and pain points. It also includes market research to analyze the competitive landscape and identify opportunities for differentiation. The team will assess technical constraints, potential risks, and resource availability. This meticulous information gathering ensures that the proposed solution is not only technically sound but also strategically aligned with your business objectives. Think of it as creating the architectural blueprint for a skyscraper; without it, the entire structure is at risk.

The primary output of the discovery and planning phase is a set of crucial documents that will guide the rest of the project. This typically includes a detailed project scope, a preliminary budget, and a high-level timeline. A well-defined scope document clearly outlines what will be built (and just as importantly, what will not be built), preventing "scope creep" later on. This initial phase sets clear expectations, minimizes ambiguity, and provides a solid framework for making decisions throughout the development process, ensuring everyone is working toward the same, well-understood goal.

Defining Project Requirements

Once the high-level vision is established, the next step is to drill down into the specifics. This involves defining the project requirements in granular detail. Requirements are categorized into two main types: functional requirements, which describe what the software should do (e.g., "the user must be able to create an account with an email and password"), and non-functional requirements, which describe how the system should be (e.g., "the page must load in under two seconds," or "the system must be compliant with GDPR").

This process culminates in the creation of a Software Requirement Specification (SRS) document. The SRS is the project's single source of truth, serving as a formal agreement between the client and the development team. It details everything from user personas and user stories to technical specifications and data models. A comprehensive SRS document is invaluable because it eliminates assumptions and provides a clear metric against which the final product can be tested and evaluated. It is a living document that may be refined but serves as the core guide for designers, developers, and QA engineers.

Conducting a Feasibility Study

With a clear set of requirements, the next step is to conduct a feasibility study to determine if the project is viable. This study analyzes the project from several angles to ensure it's a sound investment. Technical feasibility assesses whether the proposed technology stack and expertise are available to build the software. Economic feasibility involves a cost-benefit analysis to determine if the project's expected financial returns justify the investment. Finally, operational feasibility looks at how well the new software will integrate with existing business processes and whether employees will be able to adapt to it.

The outcome of the feasibility study is a clear go/no-go decision. If the project is deemed feasible, the study will also highlight potential risks and suggest mitigation strategies. For example, it might identify a need for specialized technical talent or recommend a phased rollout to ease user adoption. By addressing these potential roadblocks upfront, the feasibility study significantly increases the probability of a successful project outcome, ensuring that you don't invest time and resources into an idea that is unworkable in practice.

Design and Prototyping: Visualizing the Solution

Once the project has a green light and a clear set of requirements, the process moves from the abstract to the tangible. The design and prototyping phase is where the software's look, feel, and flow come to life. This stage is led by User Interface (UI) and User Experience (UX) designers who act as the advocates for the end-user. Their mission is to create a product that is not only visually appealing but also intuitive, efficient, and enjoyable to use. Ignoring this phase can result in a powerful application that no one knows how to use, completely defeating its purpose.

The distinction between UI and UX is fundamental. UX design is the science of making a product easy and logical to navigate. UX designers focus on the overall journey, creating user flows, information architecture, and wireframes (basic structural blueprints) to ensure the user can achieve their goals with minimal friction. UI design, on the other hand, is the art of creating a visually engaging interface. UI designers work on the aesthetics, choosing color palettes, typography, iconography, and creating the high-fidelity mockups that look like the finished product. A great product requires both an intelligent UX and a beautiful UI.

This phase is highly collaborative and iterative. Designers will present their work, gather feedback from stakeholders, and refine their concepts. The goal is to validate the design direction before investing heavily in development. By creating interactive prototypes—clickable mockups that simulate the final product's functionality—teams can conduct user testing early in the process. This allows them to identify and fix usability issues when changes are still cheap and easy to make, saving significant time and money down the line.

Crafting the User Experience (UX) and User Interface (UI)

The process typically begins with UX design. UX designers map out the entire user journey, thinking through every possible interaction a user might have with the software. They develop low-fidelity wireframes, which are simple, black-and-white layouts focused purely on structure and element placement. These wireframes help stakeholders visualize the application's flow and functionality without the distraction of colors or graphics, ensuring the core logic is sound.

Once the wireframes and user flows are approved, the UI designers take over. They apply the branding, color scheme, and typography to transform the structural blueprints into polished, high-fidelity mockups. These mockups are pixel-perfect representations of what the final software will look like. The UI designer ensures visual consistency across the entire application, creating a cohesive and professional look that builds user trust and reinforces brand identity. This synergy between UX and UI is what separates a mediocre product from an exceptional one.

Building Interactive Prototypes

A static mockup can only communicate so much. To truly understand how a product will feel in a user's hands, designers create interactive prototypes. Using tools like Figma, Adobe XD, or InVision, they link the high-fidelity mockups together, allowing stakeholders and test users to click through the application as if it were a live product. This provides a realistic simulation of the user experience, revealing awkward navigations or confusing layouts that aren't apparent on a static screen.

These prototypes are invaluable for gathering early feedback. They can be put in front of real users to observe how they interact with the design. Do they find the "checkout" button easily? Do they understand what a particular icon means? The insights gained from this user testing are gold. It allows the design team to iterate and refine the user experience based on real-world data, not just assumptions. This ensures that what gets built is validated, user-centric, and truly solves the problem it was designed for.

Development and Coding: Bringing the Vision to Life

With a validated design and a detailed blueprint in hand, the project moves into the development and coding phase. This is the heart of the construction process, where software engineers take the designs and requirements and translate them into functional code. It's the longest and often most resource-intensive phase of the project, where the abstract vision is meticulously assembled into a working piece of software. The team of developers, often split between front-end and back-end specialists, begins to build the application piece by piece.

Modern software development rarely follows a rigid, linear path. Instead, most teams adopt an Agile development methodology, such as Scrum or Kanban. Unlike the traditional Waterfall model where each phase must be completed before the next begins, Agile is an iterative approach. The project is broken down into small, time-boxed cycles called "sprints," which typically last two to four weeks. At the end of each sprint, the team delivers a small, functional increment of the product. This approach allows for flexibility, continuous feedback, and the ability to adapt to changing requirements.

This iterative nature is a key advantage of Agile. It means the client can see and test parts of their software early and often, rather than waiting until the very end of the project. Regular sprint review meetings allow stakeholders to provide feedback, which can then be incorporated into the next sprint's plan. This collaborative loop ensures the final product remains aligned with the business vision and avoids any major surprises at launch. It fosters transparency and keeps the project on track by delivering measurable progress at a steady cadence.

Front-End and Back-End Development

Custom software development is typically divided into two main areas: front-end and back-end. Front-end development, also known as client-side development, focuses on everything the user sees and interacts with in their browser or on their device. Front-end developers use languages like HTML for structure, CSS for styling, and JavaScript for interactivity. They use modern frameworks like React, Angular, or Vue.js to build responsive, dynamic, and fast user interfaces based on the UI/UX designs.

Back-end development, or server-side development, is the engine that powers the application. It's the part that users don't see but is responsible for all the logic, data processing, and communication with the database. Back-end developers use languages such as Python, Java, Ruby, or Node.js to build the server, application logic, and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) that the front-end consumes. They also manage the database (e.g., PostgreSQL, MySQL, MongoDB) where all the application's data is stored and retrieved. The front-end and back-end work in constant communication to deliver a seamless user experience.

Version Control and Collaboration

When multiple developers are working on the same project, it's crucial to have a system to manage code changes and prevent conflicts. This is where version control systems come in. The industry standard is Git, a distributed version control system that allows developers to track every change made to the codebase. It lets them work on different features in parallel on separate "branches" and then merge their changes back into the main codebase in an orderly fashion.

Platforms like GitHub, GitLab, and Bitbucket are built on top of Git and provide a centralized hub for hosting code and facilitating team collaboration. They offer tools for code reviews, where other developers can inspect and comment on code before it's merged, ensuring higher code quality and knowledge sharing. These platforms also include issue tracking and project management features, integrating the entire development workflow into a single, cohesive system. This structured collaboration is essential for building complex software efficiently and maintainably.

Testing and Quality Assurance (QA): Ensuring a Flawless Product

Development and testing are not two separate, sequential steps; they are parallel processes that go hand-in-hand throughout the development cycle. The goal of the Quality Assurance (QA) phase is to identify, document, and help resolve defects (bugs) in the software. A dedicated QA team acts as the ultimate user advocate, rigorously testing the application to ensure it meets the specified requirements, is free of critical errors, and delivers a high-quality user experience. The mantra is to find and fix bugs as early as possible.

The QA process is systematic and multi-layered. Testers create detailed test plans and test cases based on the SRS document. They then execute these tests across different devices, browsers, and operating systems to ensure consistent performance. Both automated and manual testing techniques are employed to cover as much ground as possible. Automated scripts can run repetitive tests quickly, while manual testers can explore the application more creatively, looking for usability issues and edge cases that an automated script might miss. This comprehensive approach is key to shipping a polished, reliable product.

Types of Software Testing

The QA process involves several different types of testing, each with a specific purpose. Unit testing is performed by developers to verify that individual components or functions of the code work correctly in isolation. Integration testing follows, ensuring that these individual components work together as a group. Finally, system testing evaluates the complete, integrated software as a whole to check if it meets all the specified functional and non-functional requirements.

Beyond these foundational tests, several other critical tests are performed. Performance testing checks the software's speed, responsiveness, and stability under a heavy load to ensure it can scale. Security testing proactively identifies and patches vulnerabilities to protect the system and its data from malicious attacks. The final and one of the most important steps is User Acceptance Testing (UAT). In this stage, the software is handed over to the client or a group of end-users to validate that it meets their business needs and is ready for release.

Comparison of Key Software Testing Types

To provide a clearer view, the table below outlines the primary types of testing involved in custom software development.

| Test Type | Purpose | Who Performs It | When It Happens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Testing | Verify individual components or functions work as expected. | Developers | During development |

| Integration Testing | Ensure different modules or services work together correctly. | Developers / QA | After unit tests |

| System Testing | Test the complete, integrated software as a whole. | QA Team | Before UAT |

| User Acceptance Testing (UAT) | Validate that the software meets business requirements. | Client / End-Users | Before deployment |

| Performance Testing | Check for speed, responsiveness, and stability under load. | Specialized QA | Before deployment |

| Security Testing | Identify and fix security vulnerabilities. | Security Experts / QA | Throughout the cycle |

Deployment, Maintenance, and Support: The Journey Continues

The moment has finally arrived: after months of planning, designing, coding, and testing, the software is ready to be released to its end-users. This is the deployment phase, where the application is moved from a controlled development environment to a live "production" environment, making it accessible to the world. While it may feel like crossing the finish line, deployment is more accurately the starting line of the software's active life. The real test begins when real users start interacting with it in a live setting.

Deployment is a carefully orchestrated process. The rise of DevOps culture has introduced a high degree of automation into this phase, minimizing the risk of human error. Automated scripts can handle the entire process of setting up servers, configuring databases, and pushing the new code, making deployments faster and more reliable. Modern strategies like blue-green deployment (where a new version is deployed alongside the old one, allowing for an instant switch or rollback) or canary releases (where the new version is rolled out to a small subset of users first) are used to minimize downtime and risk.

Once deployed, the journey is far from over. All software requires ongoing maintenance and support to remain functional, secure, and relevant. The digital world is constantly changing; operating systems get updated, new security threats emerge, and user expectations evolve. A dedicated team must be in place to monitor the application's health, fix any new bugs that appear, apply critical security patches, and provide support to users. This continuous cycle of monitoring and improvement is crucial for the long-term value and viability of the custom software. Feedback from live users becomes the fuel for future iterations, often leading back to the planning phase for new features and enhancements.

The Deployment Process

Deploying software is a technical procedure that requires precision. The code, which has been living on developers' machines and staging servers, must be carefully packaged and transferred to the production servers that will serve it to the public. This involves more than just copying files; it includes running database migrations, setting up server configurations, and configuring network settings.

To manage this complexity, modern teams use Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) pipelines. These are automated workflows that build, test, and deploy code every time a change is made. CI/CD not only speeds up the release process but also enforces quality checks at every step, ensuring that only well-tested code makes it to production. This automated, systematic approach is fundamental to deploying with confidence and consistency.

Ongoing Maintenance and Iteration

Maintenance is a proactive effort to keep the software healthy. This includes corrective maintenance (fixing bugs discovered after release), adaptive maintenance (updating the software to work with new environments, like a new OS version or browser), and perfective maintenance (making improvements to performance or maintainability). Neglecting maintenance is like never changing the oil in a car; the system will eventually degrade and fail.

Beyond keeping the lights on, the post-launch phase is about iteration and evolution. By collecting user feedback through support tickets, surveys, and analytics, you can understand what's working and what isn't. This data is used to build a product roadmap—a strategic plan for future features and improvements. This cyclical process of shipping, measuring, and learning ensures that the software continues to evolve and deliver increasing value to both the users and the business over time.

—

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How long does it take to build custom software?

A: There is no one-size-fits-all answer. The timeline for building custom software varies dramatically based on its complexity, the number of features, and the size of the development team. A simple Minimum Viable Product (MVP) might take 3 to 6 months, while a large, complex enterprise-level system could take a year or more to build. The Agile methodology allows for a faster initial release, with more features being added in subsequent iterations.

Q: How much does custom software cost?

A: Similar to the timeline, the cost is highly dependent on the project's scope. Factors include the complexity of features, the technology stack chosen, UI/UX design needs, and the geographic location and seniority of the development team. Costs can range from tens of thousands of dollars for a small application to several hundred thousand or even millions for a large-scale, enterprise-grade platform.

Q: Is custom software better than off-the-shelf software?

A: It depends on your needs. Off-the-shelf software is a great choice for standard business functions (e.g., email, basic accounting) because it’s cheaper and immediately available. Custom software is better when you have unique business processes that off-the-shelf solutions can't support, when you need to integrate multiple systems, or when you want to build a unique product that provides a competitive advantage. It offers scalability, full ownership, and is tailored precisely to your workflow.

Q: What is a Minimum Viable Product (MVP)?

A: An MVP is a version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least amount of effort. It’s not a "half-built" product; it's a strategic version that includes just enough core features to be usable by early adopters and solve a primary problem for them. The feedback gathered from MVP users is then used to guide future development and ensure you are building something people actually want and will use.

—

Conclusion

Building custom software is a complex but immensely rewarding endeavor. It's a disciplined journey that transforms a unique business vision into a powerful, functional, and scalable digital tool. From the critical initial Discovery and Planning phase to the creative Design and Prototyping stage, through the intricate Development and Coding, the rigorous Testing and QA, and finally into the ongoing cycle of Deployment and Maintenance, each step is essential for success.

The process is fundamentally a partnership—a close collaboration between the business stakeholders and the technical team. By understanding this step-by-step guide, you are better equipped to navigate this journey, ask the right questions, and contribute effectively to the creation of a product that not only meets but exceeds expectations. A well-executed custom software project is more than just an expense; it is a strategic investment in efficiency, innovation, and the long-term success of your business.

***

Summary

This article, "How Custom Software is Built: A Step-by-Step Guide," provides a comprehensive overview of the entire Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC). It demystifies the process by breaking it down into five core, sequential phases. The journey begins with Discovery and Planning, a foundational stage for defining project goals, requirements, and feasibility. It then moves to Design and Prototyping, where UI/UX designers create the visual blueprint and interactive models of the application to ensure it is user-friendly.

The third phase is Development and Coding, the core construction stage where engineers write the code for both the front-end (what users see) and the back-end (the server-side logic), often using Agile methodologies for iterative progress. This is followed by the crucial Testing and Quality Assurance (QA) phase, where the software is rigorously tested for bugs, performance, and security to ensure a high-quality product. Finally, the guide covers Deployment, Maintenance, and Support, explaining that launching the software is not the end but the beginning of its active life, requiring ongoing updates and iteration based on user feedback. The article emphasizes that building custom software is a structured, collaborative, and cyclical process that, when done right, provides significant strategic value to a business.